Vambéry, Armin (Hermann) 1832 - 1913

Images: Vambéry Armin and contemporary fashion

in Persia and Schiraz respectively

When I visited Hungary and Budapest in 1998, I tried to remember any and every connection to Hungary I’ve ever had. However, they were few. As a Swede, the deeds of Raoul Wallenberg during the second world war naturally came into mind. And my teacher in grammar school who fled her native country in 1956, after the uprisings in Budapest. But that put an end to my list. Being very interested in 19th century explorers though, I remembered the name Vambéry, although I couldn’t place him with certainty. I asked my Hungarian friend Eszter about him, but he was unknown to her. So I decided to investigate this further upon my return to Sweden. The following facts were easily found:

Vambéry, Armin (Hermann), born 1832, dead 1913, Hungarian orientalist and explorer, professor in oriental languages in Budapest 1865. In the early 1860ies he traveled through Armenia, Persia and Turkestan and thanks to his unusual proficiency in languages, he was able to gain a deeper insight into the local customs than any European had before. He published his recollections from his travels in Central Asian Journey 1863 (1865) and Journey in Persia (1867). In 1886 he published Arminius Vambéry, his Life and Adventures written by himself. His linguistic works are mainly on Turkish. His address was No 24 Ferenc Jozef-rakpart in Budapest.

But this was a mere abstract of his life, and I wanted to go further into detail and that ended up with two fine sources to dig out of. Firstly, I came across an original edition of Vambéry’s second book, translated to Swedish and printed in 1869 (which by the way probably is the most valuable volume I own). And secondly my old hero, the magnificent Swedish explorer, the late Sven Hedin (who for the record is the man who has mapped the largest portions of the earth’s surface single-handedly) again proved valuable. After Hedin’s very first trip in Persia in 1886, at the age of 21, he befriended Vambéry in Budapest upon his return to Sweden and until the death of Vambéry, the friendship lasted. Hedin also wrote about Vambéry and from these two sources, I have extracted, compiled and translated the following:

In the 1860ies and 1870ies, the name Vambéry was famous all over the world. Today his name is forgotten and few are those who have heard the dying echo of his fairytale adventures and bold walks as dervish, or religious beggar, trough the countries of Asia who were still unknown in his time.

Vambéry was born in 1832 and came from a poor Jewish home in Hungary. His real name was Hermann Bamberger, which he transformed to the, due to his later fame, more well-sounding Vambéry Armin, or Arminius in England. His parents were poor. At the age of five, he lost his father and his mother re-married. Already as young boy he was attracted, maybe due to his oriental origin, to the fairy lands of the east. In his childhood he was limping, and had to use a crutch. But he must also have been very determined, because at the age of ten he threw away his crutch and forced himself to walk like ordinary people. He was abandoned at the age of twelve, and began working for a tailor, and later as a private tutor for an inn-keeper. With small savings, he turned to the high-school of Pressburg and learned Latin. Thereafter, he walked with his rucksack to Vienna, Prague and other cities where he lived with priests whom he entertained by reciting the works of roman writers.

In 1847 he returned to teaching and taught languages for ten hours a day and used the rest of his time to study Slavonic languages, Greek, French, English, Danish and Swedish. He could endlessly recite from the works of Lomonosov, Pusjkin, Tegnér, Andersen and Oelenschläger. He dreamt of Asia, land of adventures and could never grow tired of Arabian Nights. He learned Turkish thoroughly, and he found it easier than other languages due to its relation to the Magyar language, and he studied its literature and poetry. Soon he could write Arabian and his greatest sorrow was the fact that he could not afford a Turkish dictionary. But already in 1858, he published a German-Turkish word-book.

22 years old and with 15 forints in his pocket, he took a Danube-ferry to Galatz and paid for meals and a foredeck ticket by entertaining the passengers with reading Petarca, Tasso and Tegnér by heart. The journey went on to Constantinopel where he lived as a Turk and gave lessons in French to the son of a pascha. Due to his language skills, he got to meet and befriend a lot of important Turkish people and through his friendship with a certain Ahmed Effendi from Baghdad and Mollah Khalmurad from Bokhara, he learned more about Asian ways of thinking and grew more eager to travel in central Asia. During this time he was honored by becoming a corresponding member of the Hungarian Board of Sciences and received a grant of 600 forints to explore the inner parts of Asia. As a child he lived in poverty, as a youngster he worked hard to make a living, while maturing he became a distinguished guest in the Istanbul jet-set and now, at the age of 30, he had no doubts about settling for a journey on unpaved roads, in the disguise of a beggar-monk, to his dreams.

Image: Kasri kadschar, a royal palace close to Teheran

He continued from Istanbul to Trebisond and on the 21st of May 1862 he rode into Teheran, still without disguise, accompanied by a few Armenians. He didn’t hide his fear of being ambushed by Kurdian robbers but he made it across the foot of Ararat to the Persian border and even escaped a flock of wolves before he found himself in Khoy, the first village in the kingdom of the shah.

In Tabris - where he stayed for a couple of weeks in order to understand the Shia belief, which differs a lot from the Sunni belief to which he, as a Turk, belonged - he was able to witness the feast which celebrated the shah’s eldest son, Mussafer-ed-Din Mirzas, becoming heir of the throne.

Vambéry reached Kasvin in the month of Moharrem, when the shia Muslims celebrate the sad memory of the death of Imam Hussein, by injuring themselves with knives. He had a letter of recommendations from Istanbul to the Turkish minister in Teheran, Haidar Effendi, and was received in a splendid way. But his new Turkish friends warned him strongly against anything as foolish as a journey into the wild and savage central Asia.

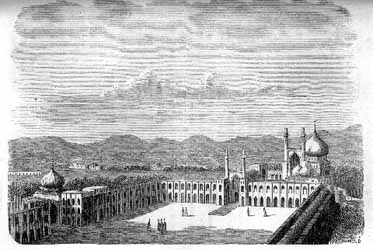

Image: View over Meidán-i-schah (The Royal Market) in Isfahan

He left Teheran on the 2nd of December 1862 with an entourage of pilgrims and wizards from Meshed and Baghdad and never missed his newly obtained duty to pray at several times daily. These literate wanderers of the Khoran passed the holy grave of shah Abdul Azim and the night thereafter they met a stinking caravan of corps en route to the grave of Imam Hussein in Kerbela. Soon thereafter they saw the green cupolas of Fatima’s grave in Kum in the south. Since he acted as a Muslim and dervish of the Sunni belief, Vambéry was admitted without questions into the holy grave, otherwise closed to those unfaithful. After two weeks in the capital of the great shah Abbas, Isfahan, they continued. Now with an entourage of 60 travelers and 150 animals, they proceeded across Kuminschah, Jesdekast and Abada to Pasergade and the grave of Cyri. Vambéry obviously felt no repulsion against European names carved into the marble wall, since he added his own.

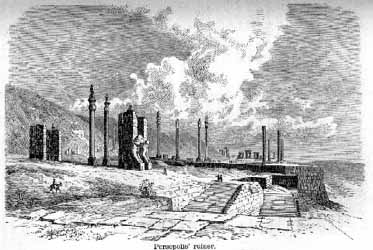

Image: The ruins of Persepolis

He rode alone over the Mardescht-plateau to Persepolis. He wrote about Schiras, the city of roses and parks, with amazement and he loved it so much that he stayed there for three months. During this time he made the acquaintance of the Swedish doctor Fagergren, a very funny episode which Vambéry later recalled like this:

"One day I heard that a man from Europe, a Swede, was living in the city and worked as a doctor. My adventurous heart made me pay him a visit but I decided, just in case, to maintain my incognito and meet him still disguised as a dervish. I entered his room with the usual greeting phrase of the dervish: ‘Ja hu! Ja hakk!’, and the good doctor immediately reached into his pocket, in order to get rid of me by a few coins - the normal way of making dervishes go away.

‘What, are you giving me money!?!’ I shouted. ‘I came to win your faith, not your money. I come from a far-away country and I’ve been sent to you by my superior in order to convert you from your false religion to the true religion of Islam. I have been ordered by the sheik of Baghdad to convert you to a Muslim!’.

To the doctor, such attempts of conversion, were by no means extraordinary and he answered with a smile: ‘All of that sounds well enough my dear dervish but it isn’t appropriate to attempt conversion in such a commanding voice, no you should only use friendly, polite and convincing words. But can you prove that your sheik has sent you and that he can perform miracles?’

‘Are you seriously questioning that? Just one syllable from the lips of my master is enough to provide knowledge in all sciences of the world and languages. You are a frengi (=foreigner) and probably speak several languages. Try me in any language of your choice.’ The doctor stared at me and it was hard for me to maintain my incognito. At last he spoke to me in Swedish, his native tongue.

Swedish, I said, I know that language as good as you. In order to prove it, I recited a few lines from Tegnérs Fritiofs Saga (an important Swedish classic). The doctor was surprised beyond recognition. He started to try me in German, and to his amazement I instantly replied in German. He was no way better off when he tried my French and English and after having tried a couple of words in several other languages, I returned to Persian and recited in a very serious way a verse from the Khoran to save his soul. The poor man was utterly amazed, but as he continued to guess my true nationality, I rushed to my feet and bade him farewell with the following words: ‘I’ll give you time until 8 tomorrow morning, to consider whether you will accept Islam or become a victim of the wrath of my master’.

The following morning, I unmasked myself and told him my true identity. The doctor was delighted and we embraced each other like brothers".

Vambéry remained a guest of Fagergren’s for six weeks and they made several excursions together. He gained several important friends and the following adventures in numerous countries were no less exciting.

In 1864 he was invited by the Royal Geographical Society to give lectures and was celebrated by the society’s president Sir Roderick Murchison, a friend of Livingstone and the great polar explorers and he warned Lord Palmerston for the Russian’s plans. Rumor had it that Vambéry was some sort of oriental spy and in his book he later jokingly remarked that the Asians suspected him for being European and in Europe vice versa. Regarding his book he said: "through my book I gained more than money - the recognition of the English audience and a reputation all over the continents of Europe and Americas". In Paris, Napoleon III made a weak impression on Vambéry. Kaiser Frans Joseph accepted him gladly and made him a professor of oriental languages at the University of Budapest. Once, when the sun would go down on him forever, he would (as he says in his book) be able to exclaim: "It was a hot, but a fin day, Sir!".

On the 12th of December 1912, at the age of 81, he ended his last letter to Sven Hedin: "Ich könnte wohl noch reisen doch die Lust fehlt mir dazu. Wenn man so viele Jahre gelebt, so viele Länder und Menschen kennen gelernt, da wird man erst recht ein stiller Derwisch, der von seiner Zelle aus die Welt beobachtet und verachtet. Mit hertzlichen Grüssen, Ihr alter Freund, H. Vambery". He died on the 15th of September 1913.

I hope this excursion into the long lost stories of the past could offer you some entertainment. According to me, Vambéry surely qualifies as a cool dude!

Täby 16th of December 1998, John Boija